A former Navy prosecutor turned Montana-based clean energy developer wants to build the first pumped hydro storage facility the U.S. has seen in years.

Battery installations are growing at a steady clip, but good old pumped hydro storage, which lifts water into elevated reservoirs for later use in generation, still utterly dominates the field. The 21.6 gigawatts of installed pumped hydro provide 97 percent of utility-scale storage on the U.S. grid, according to the National Hydropower Association.

Pumped hydro does not drive many headlines, though, because its scale and environmental implications translate into decade-long development cycles, and almost nobody tries any more.

Carl Borgquist, president and CEO of Absaroka Energy, decided to try, and he made that decision a decade ago.

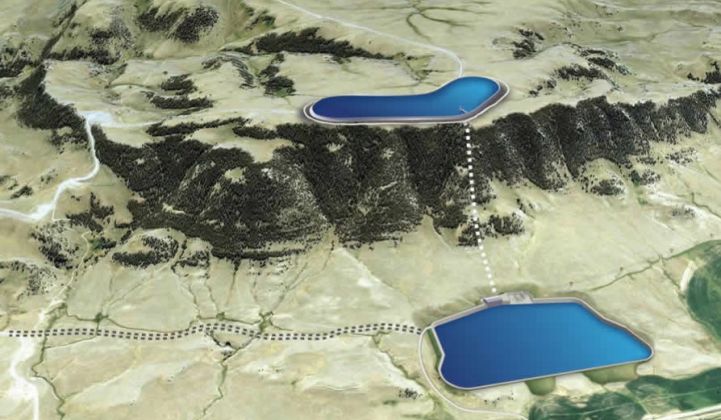

Since then, his firm has acquired rights to build Gordon Butte, a closed-loop system of two man-made reservoirs on private land in Montana, 5.5 miles from the Colstrip transmission line that shuttles renewable generation out to the utilities of the Pacific Northwest. He applied for and obtained the various state and federal certifications needed to build such a facility.

In July, Absaroka announced that Danish fund manager Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners signed on as lead equity investor.

Now, all the project needs is an offtaker — utility or otherwise — to contract for capacity, frequency regulation, ancillary services or whatever other function the plant can serve.

“Everything else is really ready to go,” Borgquist told GTM. “We just need to find the tenant for our building, so to speak.”

If a customer materializes, the project could break ground in 2020 with an expected four-year construction timeline. Doing so would lend credibility to the oft-cited but rarely enacted theory that pumped hydro offers massive untapped potential for storing clean electricity.

New century, new tech

All pumped hydro projects share certain formal structures: discrete reservoirs, difference in elevation, turbines. Absaroka's Gordon Butte will attempt to innovate on the form as the first new project of its kind since the rise of wind and solar power.

For one thing, it won't devastate any lovely riparian ecosystems. The consideration of the environmental fallout caused by dam construction brought the U.S. dam boom of the 20th century to a firm halt.

Absaroka doesn't even want to touch existing water systems, so it will build its own. The sealed reservoirs, with roughly 60 to 80 acres of surface area, will sit across 1,000 feet of vertical difference, like “two lined swimming pools connected by a pipe,” Borgquist said. The project has a state-issued water right for the life of the facility, including an initial fill, to be followed by top-offs for the approximately 10 percent of volume that will dissipate via evaporation each year.

The equipment producing the power got a modern update, too.

Traditionally, pumped hydro facilities used a fixed-speed, reversible turbine to pump water up for charging or let it fall back down for discharging. Switching from one to another can take up to half an hour, Borgquist said.

That was fine when plants only needed to switch over predictably twice a day to store extra nuclear generation, for instance, but it's not competitive in the fast-paced world of a grid with ample intermittent renewables.

Instead, Borgquist said, this will be the first U.S. facility to install a “quarternary” architecture that pairs a turbine with a generator alongside a variable-speed motor hooked up to a pump. The three turbine sets can operate independently, which allows the plant to generate and store simultaneously. The variable-speed pumping also enables much faster changeover from storing to generating.

“The idea was to create a very flexible tool for the grid that we’re walking into," Borgquist said. "The grid that we’re walking into needs that kind of speed and flexibility.”

Absaroka partnered with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and others on a Department of Energy-funded study of more flexible pumped hydro designs. Now the company is putting that work into practice.

"It's not cold fusion"

Projects with decade-long lead times and no recent models for success can be a hard sell to investors. Absaroka nevertheless won over Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners as a backer. Borgquist attributes some of that to his team's willingness to embrace intense regulatory vetting.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has jurisdiction over hydropower projects that occupy navigable waterways, sit on public land or use water from federal dams. Gordon Butte does none of those, but the developers volunteered for FERC scrutiny anyway; the process also brought in relevant state agencies to assess the project's impacts.

“It’s a billion-dollar project, and we felt like we needed that scrutiny to attract someone like CIP,” Borgquist said. “Now we have a record, and financing parties are comfortable with the fact that we’ve been studied.”

The capital investment and regulatory hurdles are steeper than what lithium-ion battery developers face. Fast turnarounds have been a key asset for those newfangled storage facilities. But Borgquist believes pumped hydro can succeed in areas where lithium-ion grid storage is weaker.

Pumped hydro contains no harmful chemicals, and Gordon Butte, initially licensed for 50 years, doesn't face the kinds of degradation issues that lithium-ion cells suffer over time.

“We’re more complicated to permit and put in the ground, but our first major maintenance moment is at year 27, when it’s estimated that the turbines will need to be replaced," Borgquist said. "The rest of the equipment is just big valves, big pipes. It doesn’t really change, no matter how many times you cycle it.”

The biggest advantage, of course, is scale. A few record-breaking lithium-ion projects are underway at the scale of 100 megawatts with 4 hours of storage duration. Some even larger ones have been announced. Gordon Butte would offer 400 megawatts of power capacity with more than 8 hours of duration. That's a lot more room to store renewable generation.

A lot still has to go right before that happens. If it does, Borgquist hopes the project can serve as a model.

“It’s not cold fusion," he said. "We’re hoping the word gets out there and people will copy.”