Net metering allows solar system owners to reduce their bills by sending the excess electricity they generate, usually at periods of peak demand, to the grid. Their utility bills are credited at the average retail electricity rate.

And, as noted by Prometheus Institute for Sustainable Development Founder, President and Director Travis Bradford, “utilities are actually getting something of the highest value for an average price.”

But there is more to an electricity bill than that, explained Greentech Media Research Managing Director Shayle Kann as he was serving as moderator of a debate about net metering between Bradford and Westinghouse Solar CEO Barry Cinnamon at the GTM Phoenix solar summit.

A utility bill has a fixed component covering the transmission-distribution infrastructure, he said, and a charge for electricity generation. When solar system owners spin their meters backward at the full retail rate, they pay neither the generation component nor the transmission-distribution component, shifting those costs to “everybody else.”

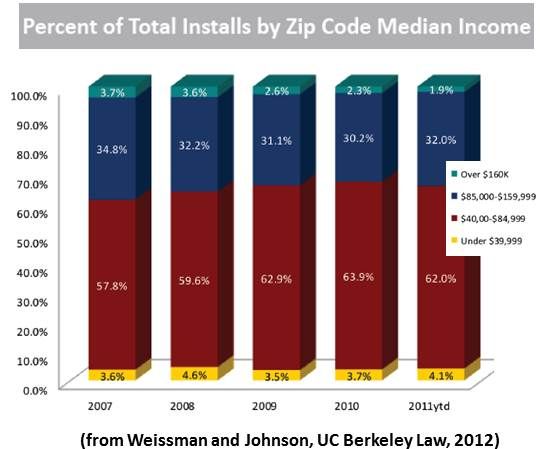

“The way the trend has been for the past twenty years,” Cinnamon said, “is that it has not been the lower income people who put in solar, and that’s why it’s so regressive.”

Utilities have taken up the cause of low-income ratepayers as a way to advocate for caps on the amount of net metering allowed.

But it is the threat to utility profits that drives their opposition to net metering, Cinnamon contended. “It’s really a debate about the current utility business model and current rate structures,” he said. Because utilities are regulated, “the more assets they have, the more profits they’re allowed to earn” and “the more revenue they’re able to bring in from selling electricity, the more profits they have.”

“Limiting net metering is a rational utility business response,” Cinnamon said, because it is “a double bad whammy for utilities,” he said. “Not only do they not to get generate profits based on their net assets, but they lose revenue simply because people are disconnected from their system and because they’re not buying electricity.”

“Let me see if I can sum up your argument in a few words,” Bradford snapped. “There is some amount of excess generation that happens during the day and that goes back into the grid [and] somehow the grid providing this battery storage for free is going to kill Grandma?”

Cinnamon persisted. “My wife gave me the energy bill for last month. The utility owes me $70.98. How are they going to come up with that money when we all put systems in?” He cited a study finding “that PG&E has a cost of $18.31 per customer per month for net metering.”

It could lead “to what some people call a utility death spiral,” Cinnamon said. “Solar costs keep coming down -- we’re doing a great job in the industry of reducing those costs. More customers switch to rooftop solar. Revenues at the utilities decline, but they still need to make certain profits, so they raise rates. The higher the rates go, the better the economics for solar go and more people go solar. This is a spiral that is not going to improve.”

Distributed generation, Bradford said, has “real benefits. We’re talking about the cost side, but we never think about these benefits.” Rooftop solar “acts as a fuel price hedge for the overall fuel mix that has a very measurable and meaningful value. It avoids losses in the system, line losses, transmission losses. It avoids additional capex.” And, Bradford added, there are environmental benefits.

“Blah-blah, blah-blah, blah-blah,” Cinnamon interrupted. “For this debate, let’s put aside all the altruistic garbage, that it benefits the environment, energy independence -- that just confuses the matter. Let’s focus on creating jobs and, better yet, let’s focus on creating utility jobs, because they are huge employers.”

“Why do you hate solar energy?” Bradford snapped. “Seems odd, given your choice of career. Afterwards, please submit your tax return so we can find out which utility you are a paid lobbyist for.”

“I’m not running for political office,” Cinnamon answered, “so I don’t need to disclose.”

Bradford turned back to the debate. “This is money to the utilities that needs to get valued.” There are “recent studies around the value of putting zero marginal-cost renewables into the grid mix and its impact on bringing down the average clearing prices of all power.” The studies show “these benefits are extraordinarily substantial, like half a cent to a penny per kilowatt-hour to the entire grid [and] far more than the studies show of what it might cost.”

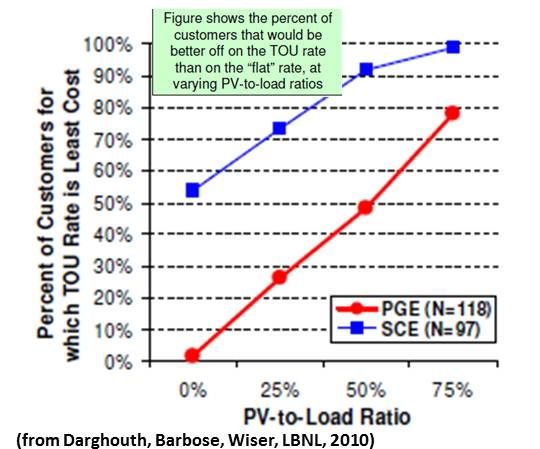

But, Bradford said, “a more fair system that uses a correct locational marginal price for what it costs and the capacity charges, and using time-of-use rates for when the stuff is generated” is complicated. “Utilities are going to end up paying more than they are currently paying under net metering.” So, Bradford said, “My advice for you and all your utility friends is to stick with the current system, keep the change and let’s get on with it.”

Because, Bradford said, “onsite storage is a way to solve this problem without net metering” that would further marginalize utilities. Rooftop system installers like SolarCity, he said, “are putting storage on systems right now as part of their package. There is no reason that’s not going to continue.” The best way to beat solar, Bradford said, is to join with it “sooner rather than later.”