Sacramento Municipal Utility District, the publicly owned utility in California's capital city, has changed its energy-efficiency metric from avoided electricity consumption to avoided carbon dioxide emissions.

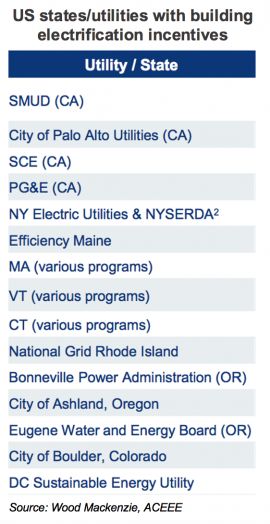

SMUD is the first utility in the country to count avoided carbon emissions from the existing building stock as part of its progress on energy efficiency. This makes building electrification central to SMUD’s energy-efficiency efforts.

The switch to "avoided carbon" is part of SMUD’s ambitious effort to accelerate the decarbonization of its existing building stock.

Measuring energy efficiency in terms of avoided CO2 emissions could be an effective way to incentivize utilities with decarbonization targets to adopt building electrification, provided that those utilities are also greening their power supply, according to a new Wood Mackenzie case study focused on the effort.

A holistic vision

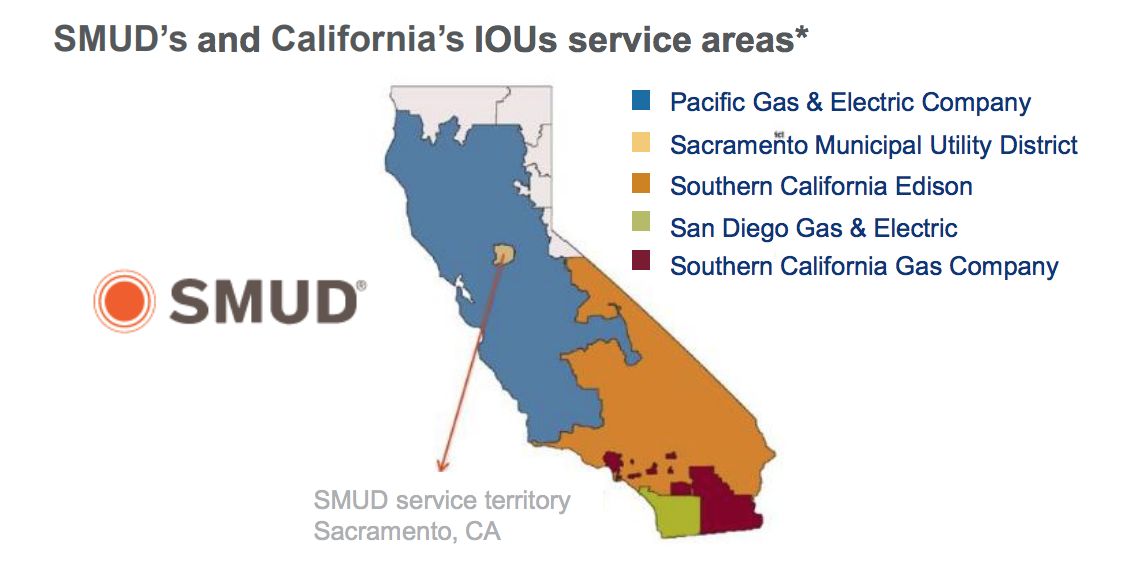

Building electrification is a core component of SMUD’s strategy to reach carbon-neutrality by 2040. SMUD expects 80 percent of buildings in its area to be all-electric by 2040, up from 17 percent today.

To prove the value of building electrification for climate-change mitigation, SMUD developed a tool to calculate the savings in terms of avoided CO2 emissions from switching to electricity over the lifetime of an appliance, taking the evolving carbon-intensity of the grid into account. Avoided carbon is a function of how clean the grid is for a specific location and of electricity’s time of use.

Unlike energy-efficiency programs that measure success in kilowatt-hours avoided, by folding building electrification into its energy-efficiency efforts, the utility is advancing energy efficiency while increasing electricity sales.

SMUD has already begun a massive effort to expand penetration of electric space and water heat pumps, induction cooktops and charging stations for electric vehicles in its service territory.

The utility’s latest integrated resource plan (IRP), which SMUD adopted in 2018 and the California Energy Commission approved in January 2020, includes numerous incentives for electric retrofits and all-electric new buildings to allow SMUD to meet its net-zero carbon target.

New state-level building standards will also be required to ensure this goal is reached, the IRP notes.

_542_461_80.jpg)

Sacramento’s heat pump decade

WoodMac’s case study highlights heat pumps as a key technology for SMUD’s and other utilities’ decarbonization efforts since home heating is a major source of emissions from natural gas. Heat pumps also bring the added benefit of increasing the efficiency of cooling, in addition to decarbonizing heating.

SMUD’s IRP estimates that over 85 percent of existing residential and 75 percent of commercial space and water heating will need to be converted from gas as a principal fuel source to electricity.

Even when relying on natural-gas-fired plants for power supply, heat pumps’ high rate of fuel-to-heat conversion (known as coefficient of performance) makes electric heat less carbon-intensive than gas heating. The peak carbon-intensity of SMUD’s grid today is already below that of an all-gas generation fleet, and it is expected to fall further over the next few decades as the utility adds renewables and demand-side resources to its grid.

The decrease in the carbon-intensity of SMUD’s grid and more heat pump installations will see a continued increase in CO2 savings.

WoodMac’s analysts also note that financial incentives for installing heat pumps are necessary to promote building electrification, as heat pumps still can’t compete with natural-gas-fueled appliances in economic terms alone due to low natural-gas prices in the U.S.

To this end, SMUD offers residential heat-pump water heater rebates of up to $2,500, as well as incentives to retrofit commercial buildings.

The size of the rebate is a key differentiator for SMUD. Its heat-pump water heater rebates are significantly higher than those offered by California’s other investor-owned utilities.

New buildings, new policy battles

The existing building stock isn’t the whole story, however. SMUD’s carbon-neutrality timeline assumes that the majority of new buildings in California will be required to be all-electric.

For new buildings, rebates, restrictions on new natural-gas hookups and all-electric building codes are the key policies at play around the country.

As of Q3 2020, 33 municipalities in California have introduced building codes that require or encourage all-electric construction. Meanwhile, the next update to California’s Title 24 building standards could mandate that all new buildings statewide must be all-electric from 2023 onward. PG&E, a utility that provides both electricity and gas, has indicated its support for the new codes.

Other gas distributors have shown less enthusiasm for California’s electrification policies. In July 2020, Southern California Gas sued the California Energy Commission in the state's Orange County Superior Court, alleging the CEC failed to produce a key report that the utility typically receives, which would detail the CEC’s strategy for taking advantage of natural-gas resources.

The tensions about electrification policies are mounting outside of California as well. States including Arizona, Oklahoma and Tennessee have already preemptively adopted legislation preventing local governments from introducing bans on new natural-gas hookups. As policies that encourage electrification and all-electric construction are becoming more widespread nationally, gas utilities are using this opportunity to lobby and fight back.

***

Fei Wang and Francesco Menonna are the authors of the Wood Mackenzie insight SMUD’s Building Electrification Strategy: A Grid Edge Case Study.